[‘History of US healthcare: How we got to the healthcare we have today’ was originally delivered as a presentation at Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University. Jordan Halevy, MS1, is the BRI chapter founder and president there. You can view Jordan’s video here.]

[‘History of US healthcare: How we got to the healthcare we have today’ was originally delivered as a presentation at Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University. Jordan Halevy, MS1, is the BRI chapter founder and president there. You can view Jordan’s video here.]

“The US is the only developed nation without universal health coverage!”

“Free markets have failed to provide adequate healthcare.”

Sentiments like these plague any healthcare policy discussion. America is the land of markets, after all, so blame should rest squarely on misguided economic liberalization, right? People have a tendency to accept this dogma without criticism, and it is used as the springboard for many critiques of the US system. Despite this common refrain, a cursory view of healthcare’s roots reveals a steady erosion of markets.

The past century is riddled with interventions wresting control away from physicians and centralizing it in the hands of the federal government and large firms. Rather than addressing policy issues as they arise, reviewing the healthcare system in historical context can reframe the discussion, revealing its foundational problems.

Let’s take employer-based coverage as an example. Over the years, legislation has attempted to address the pitfalls in this system. Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA) placed mandates on employers to cover employees and adhere to standards of coverage. The “portability” portion of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) passed in 1996 exists to manage insurance loss due to gaps in employment. Even before HIPAA, the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) was tinkering with guaranteeing coverage after being laid off from work.

While there is no shortage of state interventions targeting this problem, many simply take for granted that health insurance, unlike every other kind of insurance, should be provided through an employer. Predictably, this decades-old issue originated with a government intervention warping the market for health insurance.

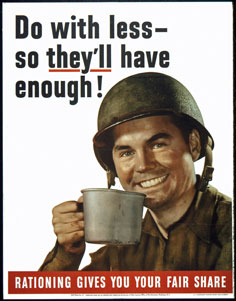

As World War II raged on abroad, the home front grappled with shortages and rationing to support the war effort. Although most economists today would agree that price and wage controls do not achieve their stated goals (nor do they contain inflation), the FDR administration was not shy about managing the economy. The Stabilization Act of 1942 was passed to combat inflation by fixing salaries at their current level. What happened next fit the classic case of a political cure being worse than the disease it tried to treat.

As World War II raged on abroad, the home front grappled with shortages and rationing to support the war effort. Although most economists today would agree that price and wage controls do not achieve their stated goals (nor do they contain inflation), the FDR administration was not shy about managing the economy. The Stabilization Act of 1942 was passed to combat inflation by fixing salaries at their current level. What happened next fit the classic case of a political cure being worse than the disease it tried to treat.

Employers were now unable to compete in a market by bidding up wages to attract prospective employees. The market, however, found new ways to operate around the constraints imposed on it. Health insurance was offered as a fringe benefit in addition to the artificially capped base salaries to attract employees, and thus the widespread use of employer-based coverage was born. At first, this could have been just one of many ways that individuals chose to get health insurance, but subsequent rulings entrenched it as the most economically viable method of getting insured. A 1943 War Labor Board decision confirmed that health insurance was exempt from wage controls, and the Revenue Act of 1954 confirmed that such fringe benefits were always tax deductible. By preferentially excluding health insurance from taxation as long as your employer bought it for you, the system exploded in popularity. The rest is history.

It’s easy to lose sight of the forest for the trees when debates on healthcare neglect how we arrived at the current system today. Employer-based coverage is an artificial construct wrought by government, and prudent policy can undo this mistake. There are numerous battles fought over healthcare that would be moot if bad policy like this was corrected at the root. When looking at cases like Burwell v. Hobby Lobby or the Little Sisters of the Poor contesting mandates on providing contraception, these clashes only exist because people have been herded into a model that places them at the mercy of their employer for insurance. Were this not the case, health insurance would be independently obtained, business owners would not be compelled to violate their consciences, and employees would not be forced to accept coverage conditional on the conscience of their employer.

Instead of looking for what can be done to fix the ills of our healthcare system, perhaps it is time to look at what disastrous legislation can be undone.